Morse, Tolkowsky, Higuchi and Other Revolutionaries

There were a few main players through history that had a hand in development

of today's Super Ideal Cut diamonds. It is curious that three men from different

continents and different time periods could be so influential in taking us to

where we are today. In America in the 1870s, Boston cutter Henry D. Morse

introduced the concept of cutting diamonds (and re-cutting) for “beauty

verses weight” and pioneered a cutting style that would later become the

Fig 1-1

American Cut. He and his colleagues produced some revolutionary innovations

that would forever change the diamond world. The contrary idea of sacrificing

valuable rough to produce a more scientifically crafted diamond was taking

hold despite the resistance of the status quo in the cutting world.

Decades later in 1919, Belgian mathematician Marcel Tolkowsky documented

specific angles and percentages in his book Diamond Design. These top

and bottom angles would later become the basis of the cut grade system

taught by GIA as “Ideal Cut proportions” in their gemology course materials

until about 1980. Contrary to popular thought Tolkowsky’s treatise was

not his doctorial thesis nor did he himself use the word “ideal” to

describe his best cut parameters.

In the 1980s in Japan a paradigm shift was looming. Japanese gemologists,

cutters and scientists were studying the ideal cut model while experimenting

with tools that could show brilliance and light return in diamonds. A

scientist named Kazumi Okuda was key in the development of research tools

using colored reflectors. His small red-ringed loupe with Zeiss optics was

among the first tools used to observe precision of facet placement in

diamonds. Fig 1-1.

Fig 1-2

Okuda was contracted by diamond dealer and researcher, Tsuyoshi Shigetomi and

his colleague Kazuo Inoue to develop a more sophisticated reflector tool, which

led to the creation of an instrument they called the Firescope in

1984. Fig 1-2, 1-2a.

Fig 1-2a

This unique device showed a three-dimensional view of the diamond easily

demonstrating light return and light leakage in the stone. Realizing that

Tolkowsky only addressed two-dimensional modeling of the 16 main facets

and table, this instrument permitted a new three-dimensional visual view

of the whole diamond showing the interplay of all 57 facets. Japanese

cutter Kioyishi Higuchi, an early pioneer in high performance ideal cuts,

used the Firescope and experimentation to create diamonds that would produce

superior light refraction and reflection (aka light performance) while

not deviating much from the original proportions of Tolkowsky. Ultimately

the Super Ideal cut was born. These early Japanese ideal cuts were very

tight tolerance and also showed superior optical symmetry when viewed in

the Firescope. Another exciting feature of these diamonds was the perfectly

symmetrical eight-rayed star that was clearly visible in the Firescope.

Fig 1-3.

Fig 1-3

Earliest Super Ideal cut brands such as

Eightstar and

Apollon 8 surfaced in

the mid-80s. Around this time, legend has it, quite by accident someone

discovered that when one of these diamonds was viewed upside down in

the Firescope, one could see a visible pattern eight symmetrical “hearts”

through the pavilion of the stone.

Fig 1-4

This was the birth of a totally new

concept in diamonds that would become known as

Hearts and Arrows. Kinsaku

Yamashita, an associate of Shigetomi, coined the name and trade marked it

in 1988. He also is credited with development of the Hearts & Arrows viewer,

for which he received a patent in 1990. The Hearts and Arrows Viewer though

a reflector device like Firescope, this instrument allows the viewer to

analyze the physical symmetry, contrast and alignment of facets in

both the pavilion and crown of a diamond, by directing light at set angles

to catch and reflect light back from specific facets and angles in the diamond.

An early version of a Japanese Hearts and Arrows viewer like the one shown here,

was developed in Japan for use across the retail counter to show this unique

phenomenon to consumers.

Fig 1-4.

Romancing the stone- Japanese style

In Japan, in the early 1990s ideal cut diamonds were all the rage. In this

country, the second biggest diamond market, where quality, status and brand

names are in vogue consumers became big buyers of ideal cuts. Cut grades

of Excellent and later Super Excellent or Triple Excellent were much sought after.

Some ideal cuts with these grades were known to show the "Cupid effect", a

Fig 2-1

visual pattern of eight hearts while looking down through the pavilion and

eight arrows when viewing the stone in the table up position. A Hearts and

Arrows Scope was needed to show this phenomenon. These new diamonds become

known in the trade as

Hearts & Arrows.

Fig 2-2

According to both Roman and Greek mythology a person shot with Cupid's arrow

supposedly fell in love, so the link between the hearts and arrows and love

is obvious. Japanese bridal magazines, featuring these romantic jewels, sent

young couples out into the streets shopping for these exciting new diamonds.

Now, for many young buyers, ideal cutting without the hearts & arrows was

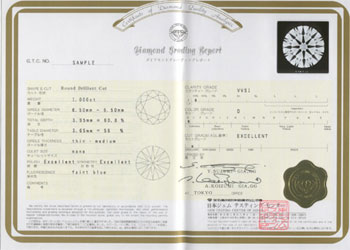

not good enough. Gemological laboratories in Japan, realizing a golden opportunity,

began issuing certificates with Excellent cut grades with photos showing the

hearts & arrows pattern. See Fig 2-1.

To assure accuracy of the new quantifying cut grades, Japanese labs used new

computerized automatic measuring systems like the Sarin Dia-mension machine

at right. Fig 2-2.